By Adam Nedeff, researcher for the National Archives of Game Show History

Legendary game show host and producer Wink Martindale passed away on Tuesday, April 15, 2025, at the age of 91. The team at the National Archives of Game Show History looks back at his life and amazing career. (Martindale completed an oral history with the Archives in 2023.)

A NAME THAT YOU’D BAT AN EYE AT

When James & Frances Martindale brought a baby boy into the world on December 4, 1933, they didn’t name him Wink. They named him Winston Conrad Martindale. But “Winston” proved too tricky to pronounce for one boy in the neighborhood, who could only sputter out “Winkie.” Winston rather liked and embraced the mispronunciation. This didn’t make his parents entirely happy—his mother would only call him Winston—but the distinctive name, later shortened to “Wink,” would make him arguably the most identifiable man in his field in the decades to come.

A BOY FROM TENNESSEE

Wink Martindale was born and raised in Jackson, Tennessee. His formative years came at the tail end of the Great Depression, and by his own admission, he had humble beginnings. He later told The Jackson Sun, “There were five of us in our small house, and my three brothers, one sister, and I lived with our parents in a two-bedroom, one-bath house with no shower. All of our water had to be heated. We poured water into a tub to take a bath. My parents bought our groceries on credit at Woody’s Grocery Store. We used to go to church every Sunday morning and evening and on Wednesday nights we went to Bible study. When school was out in the summer, we attended Vacation Bible School.”

Wink recognized a specific gift—he had an impressive voice, even as a child. He and his mother were of different minds about that. Mother thought it was a sign that he should become a preacher. Wink, a devout churchgoer, said that a person should only become a preacher if he felt called, and he admitted to his mother that he wasn’t hearing a calling. Wink, who would read the articles and advertisements from each week’s Life Magazine aloud, was fixated on radio. He held a tin can on a stick to serve as his microphone as he reported the news and paused for commercials, straight out of the magazine in his hands.

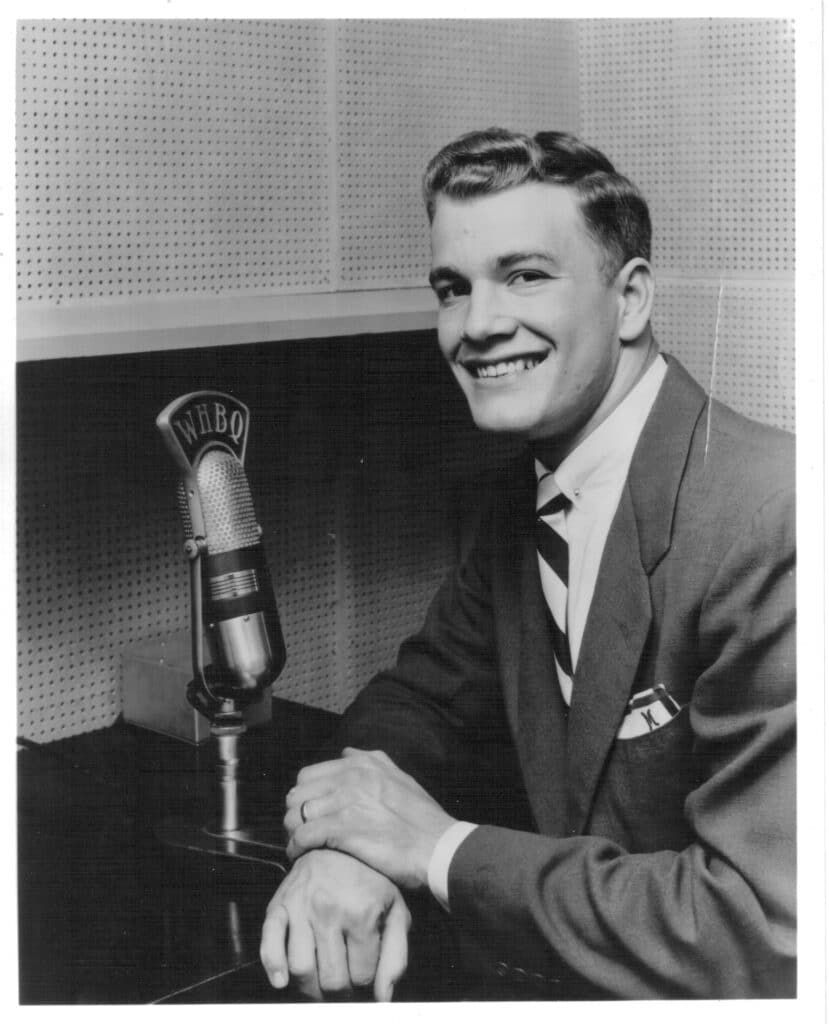

As it happened, his Sunday school teacher owned a radio station, and at age 17, Wink became an announcer at WPLI-AM, and then WTJS, where he did sportscasting, and then WDXI, all in Jackson, Tennessee. Wink attended classes at Lambuth College while working at WDXI, but when a job opening came up in the big city—in this case, Memphis—he dropped out and became a morning DJ at WHBQ-AM.

MARS-TINDALE

Wink was probably the busiest 19-year-old in Memphis. Every day he got out of bed at 4 a.m. to host the morning radio show Clockwatchers for three hours on WHBQ. Then he went to Memphis State College to take classes in speech & drama. During the afternoon, he hosted a children’s television show, Wink Martindale and the Mars Patrol. Each day, Wink donned a space suit and climbed into a small rocket ship with a group of children, “blasting off” into an installment of the Flash Gordon movie serials from the 1940s, before returning for a final segment where Wink would share some facts about outer space.

ALL SHOOK UP

In the 1950s, dozens of television stations across the station had the same basic format for an afternoon show; teenagers would dance to Top 40 hits being played by an area disc jockey who served as the host. Dick Clark’s Bandstand out of Philadelphia would become the most famous of these shows, but Wink hosted substantially the same show in Memphis, Top Ten Dance Party.

Because Memphis had become a hub for rock and country music, music stars would frequently drop by Top Ten Dance Party for a live interview. At the time, most live local television programs were not recorded. With impressive foresight, a staff member at Top Ten Dance Party told Wink that it might be a good idea to preserve one upcoming episode. Elvis Presley had given his word that he would indeed come to the studio for an interview, as a personal favor to Wink, who had always given his records plenty of airplay.

Wink hired a photographer named Bob Zimmerman to film a 1956 episode in which Elvis Presley came to the studio for his first interview. Wink and Elvis would never cross paths on television again. The singer’s legendary manager, Colonel Tom Parker, was furious that Elvis had granted Wink a free appearance on television, and had done so without Parker’s knowledge.

WINK OUT WEST

Wink had been given some unlikely breaks while in Memphis. In 1958, he received a surprising phone call from a film producer offering him a role in a low budget feature, Let’s Rock. Despite the fact that Wink wasn’t a national name yet, he got to play himself in the movie. His character’s name was Wink Martindale and he was the host of an afternoon teenage dance show. Wink even got to sing in the film, although he was the first one to call himself “a lousy Elvis Presley imitation.”

He became restless in Memphis and his boss felt Wink was capable of building a big career for himself in Los Angeles. Wink’s boss pulled some strings to help him secure a job at Los Angeles radio station KHJ, and Wink made his big move in 1959. Wink wound up meeting his boss’ expectations and probably exceeding his own. As in Memphis, he had a regular disc jockey shift plus a weekly TV teenage dance show, The Wink Martindale Dance Party.

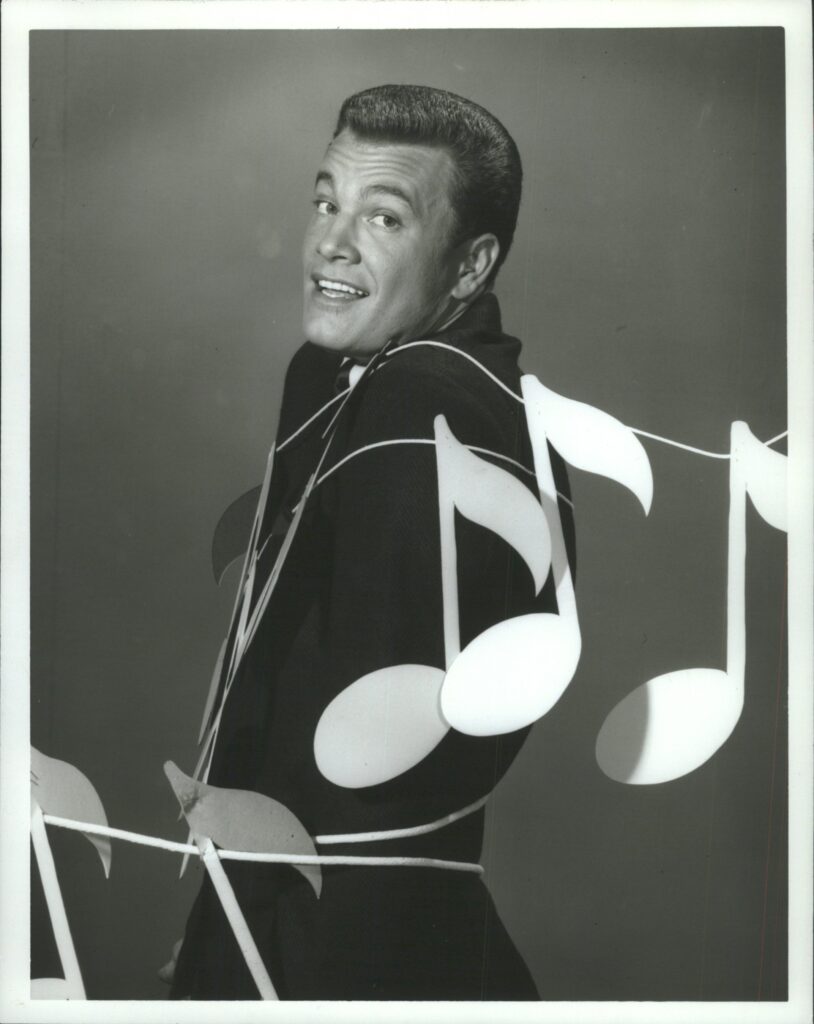

Dot Records had been a fledgling company when Wink had given some of their releases exposure on his Memphis TV show a few years earlier. Dot’s president never forgot the favor, and he felt Wink had some potential for a music career, even though Wink himself strongly disagreed. Wink recorded a cover of a single by T. Texas Tyler that had sold pretty well in 1948.

“Deck of Cards” was the name of the piece; it wasn’t exactly a song; Over a hymnal chorus of “Ooooooooh’s,” Wink narrated the story of an illiterate soldier who brings a deck of cards to church instead of bringing a prayer book, because he’s given a Biblical meaning to each card in the deck. “Deck of Cards” was a surprise hit, reaching #4 on the Billboard charts and eventually going gold with sales in excess of one million. No one was more surprised than Wink, who ended up performing the song on The Ed Sullivan Show, the ultimate milestone for show business success at the time.

Wink would go on to release dozens of singles, plus five albums, but none of these efforts ever came close to the success of Deck of Cards. Wink was disappointed but not devastated; the success of “Deck of Cards” blindsided him and he had never expected to make a career for himself as a singer in the first place. That somebody wanted him to record songs was exciting enough; that even one of them had a million buyers was a thrilling bonus.

WINK FOR THE WIN

Wink had become a fan of Password with Allen Ludden in the early 1960s. Wink may have been joking, but he would say in later years that he had read a magazine article where Allen Ludden explained the taping schedule for TV game shows; Allen talked about how all five episodes for a week of Password were taped in a single day, leaving him six days a week to do whatever else he felt like. As Wink tells the story, he promptly called his agent and said, “Get me a game show!”

He hosted a local show in Los Angeles called Zoom, in which contestants had to guess what an object was based on an extreme close-up; the camera slowly pulled away until the object was identified. Zoom wasn’t a hit, but Wink was; in 1964, he became the host of What’s This Song? for NBC, although network executives disliked his name so much that he conceded to going by the name Win Martindale for the only time in his career.

A NOT-SO-DRY SPELL

Wink’s shows in the late 1960s were decidedly more “miss” than “hit.” He had a brief tenure hosting two game shows for Chuck Barris that even Wink would acknowledge were a bit odd for their own good—Dream Girl of ’67 and How’s Your Mother-in-Law? In 1970, game shows were in a bit of a dry spell. Only two game shows would premiere that calendar year—Words and Music, another song-naming game. The other was Can You Top This?, a revival of an old radio show in which home viewers submitted jokes by mail, and a panel of comedians tried to improvise jokes based on the same subject matter; the home viewer won prizes for every comedian who failed to get a bigger laugh than the original joke.

1970 didn’t exactly feel like a dry spell for Wink; he was host of both Words and Music and Can You Top This?

THE NEXT GAME ON DECK

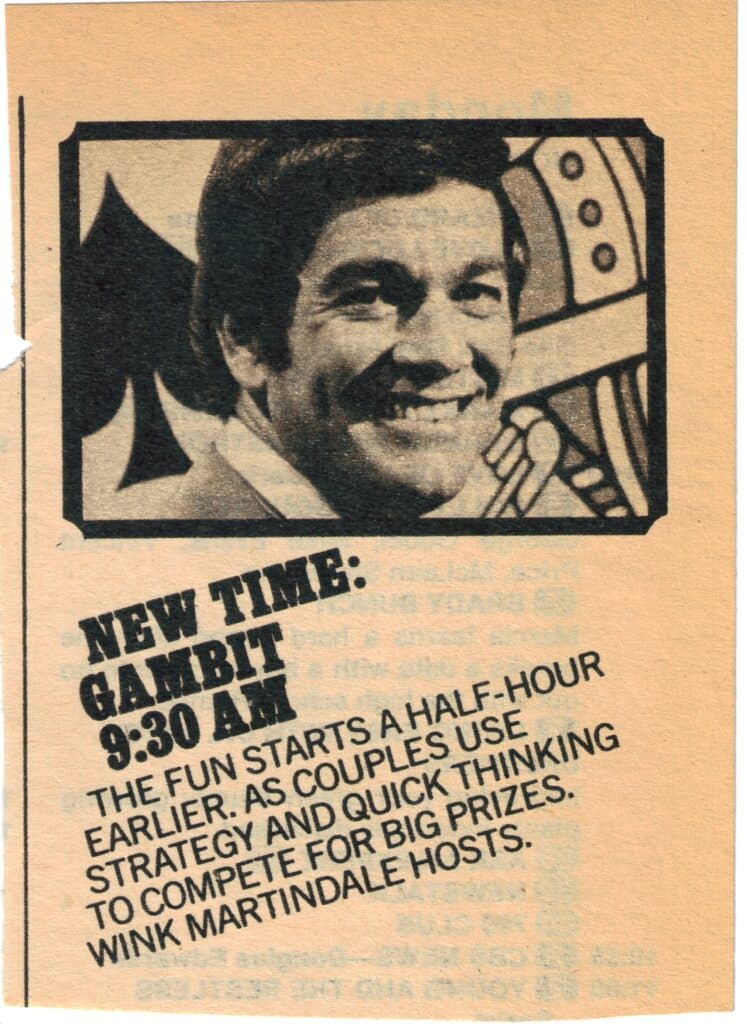

In 1972, Merrill Heatter-Bob Quigley Productions received word that CBS was looking to revitalize their flagging daytime schedule with game shows, and sold an idea to the network that they called Gambit. Dick Clark auditioned for host but apparently wasn’t quite what Heatter-Quigley was looking for. Jed Allan of Celebrity Bowling won the job, but on the day of taping for the pilot, he showed up looking extremely irritated about something, and his attitude was so off-putting that Heatter-Quigley changed their minds and replaced him.

A 1972 interview with Jed Allan lends some clue about what was bothering him. He told a reporter, “I don’t want to become typed as a game show host. I want to act. Look what happened to Peter Marshall—he’s a very good actor. Since he’s been so successful with The Hollywood Squares, nobody will let him act.”

With Celebrity Bowling already putting him on TV screens as a master of ceremonies every week, Allan, it can be speculated, probably reasoned that hosting TWO game shows at once would probably end his acting career, and he probably wanted to get out of Gambit.

The job went to Wink Martindale, a talented host in search of a hit. In the past decade, he had hosted five games, none of which made it to a full year on the air. But good things come to those who wait, and Wink had waited long enough for a game like Gambit.

Married couples competed against each other in a game that combined trivia with blackjack. Heatter-Quigley, which had previously given the nation a giant board game on Video Village and a giant tic-tac-toe grid on The Hollywood Squares, now presented a game that made use of a massive deck of playing cards; but other than the size, it was, as Wink reminded viewers at the top of the show, “a normal deck of 52 playing cards.”

A correct answer earned a playing card for a couple, with the game going to the couple that came closest to 21 without going over; twenty-one on the nose won a cash jackpot. Two out of three games won the match and a chance to pick prizes from a 21-square board. The couple had to draw a card for every prize they picked, and busting meant forfeiting all the prizes won up to that point. Getting exactly 21 in the bonus round earned a car on top of everything else. Gambit survived more than four years.

WINNING GAMES WITH A WINNING HOST

In 1978, Wink began a seven-year run at the helm of Tic Tac Dough. Slowly, Wink became subconsciously entrenched in America’s mind when they thought of game shows. The first time you heard his name, you were sure never to forget it. And with his flawless head of hair, 300-teeth smile, and a rather eccentric wardrobe—plaid, pinstripes, a suit of nearly every color in the rainbow, and occasionally, white buck shoes—he just LOOKED like a game show host. He fit the stereotypes. An extraordinary series of episodes in 1980, in which champion Thom McKee amassed $312,700 in the span of 43 victories, drew more viewers to the show and further cemented Wink’s status as the definitive host.

For all that, Wink was a lot more than an empty smile. He had a sense of humor. He would conclude every week of Tic Tac Dough with “Hat Friday,” a ritual where he wore bizarre looking hats sent in by home viewers; if a hat was too big, he thought nothing of covering his entire head with it and stumbling around the set blindly as the credits rolled. He had an affinity for puns and asked a Tic Tac Dough writer, Mark Maxwell-Smith, to prepare one for every contestant interview—and Wink was just as satisfied with an annoyed groan from the audience as he would have been with a laugh.

He had no problem drawing attention to his own mistakes; he struggled with a Tic Tac Dough question one day because he had never seen the name for a particular type of great ape written down before, and eventually sputtered out “orange-you-tan.” And there was the day when he asked a contestant to name the James Bond movie that had been released in the summer of 1983.

“In the summer of ’83?” the contestant asked for clarification.

“No, sorry, it was Octopussy.” Wink not only laughed it off, he cheerfully told TV Guide about the gaffe for their 1984 cover story about game show hosts—Wink was one of the six who appeared on the cover.

As much as the casual viewer may have viewed Wink Martindale as a stereotype, he was vocally resentful of how deeply those stereotypes imprinted themselves in show business, even among those that he felt should know better. He said in 1985, “I get sick of radio and TV commercials that do a takeoff on game show hosts. I was called to do a radio commercial, and when I saw the script was supposed to be a takeoff on a game show I just walked out. I will not do those. That bothers me. If that is what game show hosts are all about, then God forbid any of us should be doing it.”

Later in the 1980s, toy maker Galoob introduced Mr. Game Show, a battery-operated robotic toy that played a game show-style game. Mr. Game Show was designed with thick brown hair and predominant teeth; he bore more than a passing resemblance to Wink Martindale.

But as Wink implored people to understand, there was more to him—and more to game show hosts in general—then perfect teeth and immaculate hair care.

He told interviewer Michael Hill, “I guess when you do learn your craft, and you do it well, producers keep calling you. You have to be able to ad-lib, to think on your feet. And you have to have fun with people, a real affinity for people, to be able to relate one on one to the contestant. The toughest part of my job is just learning the game so you have it locked in, all the rules, without thinking about it. But one of the hardest parts is to take thirty or forty seconds and make someone who is really nervous feel at ease and at home so that they will have a good time and the audience will have a good time…A good host can make the contestant feel at ease so they can go with the flow. It’s not as easy as it looks. If it was that easy, maybe everybody would be doing it.”

LICENSE TO PRODUCE

in 1985, Wink Martindale left Tic Tac Dough after seven seasons to host a show of his own creation. Wink was reading The Los Angeles Times one morning and came up with an idea for a game.

“There was a banner headline,” he explained that year. “And I thought, if I took some of those letters out, could I still come up with the headline? I tried it on my wife when she got up and she said, ‘I don’t know what the headline says, but that would make a great game show.’ I said, ‘I’m glad you said that because it’s exactly what I had in mind.”

Wink called the game Headline Chasers. Against tough competition—many stations aired it in direct competition with Wheel of Fortune or Jeopardy!—the show lasted only one season.

In 2016, Wink remembered, “We got a phone call from the manager of the station that aired Headline Chasers in Miami, and he said, ‘Can’t you dumb it down a little bit?’ I knew we were finished.”

Wink had come up with Headline Chasers by thumbing through a newspaper. Thumbing through a magazine gave him the inspiration for his next game. He happened across an advertisement depicting license plates from all fifty states, which led to a train of thought about some of the distinctive vanity license plates he had seen. He created a game called License 2 Steal and joined forces with his former Tic Tac Dough bosses, Jack Barry & Dan Enright Productions, to sell the show to USA and Global. Under the new title Bumper Stumpers, Wink Martindale had another hit. Canadian newsman Al DuBois hosted the show in which contestants were shown a vanity license plate and had to decipher it after being told who it supposedly belonged to (for example, the license plate “KCNO” belonged to an odds-maker; the contestants had to figure out that KCNO had to be pronounced “Casino”).

WINK’S INTERACTIVE GAMES

Wink Martindale observed during the late 1980s, “Technology is very important to the audience now. You’ve got to have that modernistic stuff.”

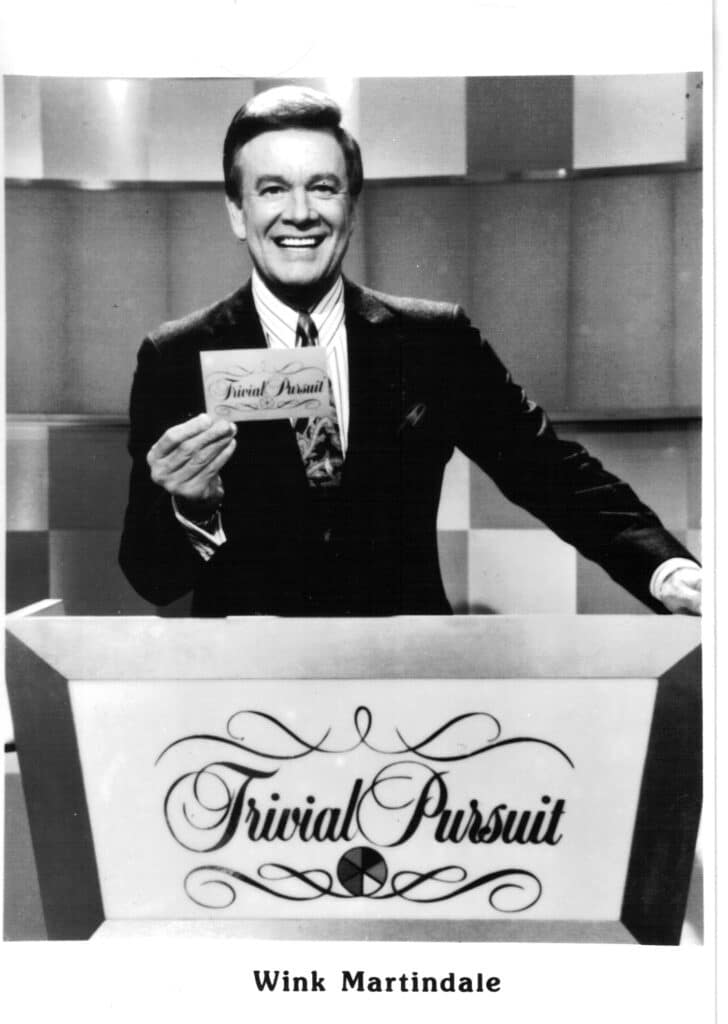

And Wink went modern in the early 1990s with an extremely ambitious idea for a 24-hour game show cable channel, simply called The Game Channel. A 1992 press kit laid out the idea; twenty-four hours of game shows, a mix of original programs and reruns, and between shows, “Playbreaks” that would allow home viewers to call a 900-number and play the games at home for prizes.

The Game Channel never got off the ground, but the notion of Playbreaks would. In 1993, Wink began a successful partnership with The Family Channel, with Trivial Pursuit, an adaptation of the board game that featured ten Playbreaks per afternoon, allowing home viewers to call in and play Trivial Pursuit at home for prizes ranging from telephones to vacations and cruises. Trivial Pursuit was such a success for the channel that The Family Channel quickly introduced three more interactive games, Boggle, Jumble and Shuffle. All four were hosted by Wink. The economics of the Playbreaks were enough to induce some salivating for production company and the channel. The 900-number charged a flat rate of $4.98 per call, with a computer system designed to accommodate 2,500 players at a time. With ten Playbreaks each afternoon, a full complement of players would net $124,000 in a single day.

If there were high rewards involved for all involved, there were high risks. The Playbreaks were so lengthy that to accommodate them, The Family Channel aired only six minutes of commercials per hour (about half of the typical amount of commercial time in an hour during 1993) and that cost needed to be offset by a high volume of calls from viewers, many of whom, admittedly, didn’t want to spend five bucks on a phone call. As an enticement, Martindale emphasized that callers would be offered coupons for deals that would offset the $4.98.

Wink admitted later, “For the average viewer, $4.98 was too much for a phone call. We couldn’t keep that going.”

DEBT

Hey, it’s that Wink guy again!

In the mid-1990s, crooner Tony Bennett unexpectedly experienced a surge in popularity among Generation Xers thanks to a concert aired on MTV. Wink Martindale received an unexpected phone call one afternoon from his agent offering him “a game show that will do for you what MTV did for Tony Bennett!”

Wink’s new game was called Debt. Buena Vista Television built a game show that was part parody and part actual game, with just a dash of social commentary thrown in. In 1995, consumers had amassed a total of $1 trillion in personal debt, a selling point that Martindale emphasized while promoting the show in interviews; it was the unlikely core premise of the show. Each episode opened with the three contestants holding up slates with their names and personal debts, arranged to look like the contestants were posing for mug shots. Each contestant fearlessly revealed what it was that caused them to go so far into the red—a car, back taxes, student loans, and, in one case, a bald man who remorselessly admitted he had spent a fortune on a toupee—and then Wink would make his entrance to inexplicable disco music on a set with 1950s-inspired décor.

“Men Who Wear Dresses,” “Must See TV If You’re Three,” “Deodorant and Antiperspirant” were some of the categories that the contestants navigated on the game board, with correct answers knocking money off their debt (with their debts actually on display and treated as their scores).

Debt was an overnight hit for Lifetime, no surprise to Wink Martindale because, he reasoned at the time, “Debt is something everyone can relate to.” The show won a CableAce Award, and the first season’s contestants were happy with the $850,000 worth of personal debt that the show erased in its first year. Debt’s contestant line rang off the hook with hopeful players getting in line for their shot. Theoretically, you could pay off your debt by doing well on Wheel of Fortune, Jeopardy!, or Supermarket Sweep, but there was something surprisingly enticing for many about going on a show called Debt, announcing your struggle to the world, and winning the chance to dig yourself out.

Executive producer Andrew Golder told the Associated Press, “Getting out of debt in some weird way is almost a new version of the American Dream. Since we’re attaching the winnings to their debt and personalizing it, a big burden is lifted off their shoulders. It’s not just ‘Here’s $6,000, go do something.’ It’s tangible, we know how you got there.”

Debt managed to make a few enemies in high places, however. It was slapped with a lawsuit from Visa after only a few weeks on the air, arguing that the show’s logo was far too similar to the credit card giant’s logo. Debt designed a new logo, only to get hit with more litigation from the producers of Jeopardy!, who felt that the game’s rules bore a few too many striking similarity to their game, forcing Debt to change its first round quite a bit before launching its second season. The show disappeared after that second season, which Wink would later attribute to a lack of focus. A new game, Win Ben Stein’s Money on Comedy Central, had become top priority for the production staff, which was running both shows, and Debt’s whimsical question writing suffered. The magic of the game had disappeared quickly.

LOOKING FORWARD TO LOOKING BACK

In the 2000s, Wink found himself in the unusual position of being a perennial nostalgia figure. Many of his television appearances in the new millennium would involve looking back on his past work. He co-hosted prime time specials showcasing memorable game show bloopers and talking at length about his old boss Chuck Barris for an E! documentary. He was a panelist for “Game Show Week” on Hollywood Squares. He appeared on morning news shows to watch clips of Tic Tac Dough and Gambit. Wink was living television history. If the subject wasn’t game shows, it was almost certainly Elvis. Wink was more than happy to talk about the friend from Tennessee that he had crossed paths with so early in a historic career.

Over a decade after Debt, Wink found himself revitalized yet again with a quirky Game Show Network series, Instant Recall, “the game show that you don’t know you’re on.” Co-created by Richard Dawson’s son Gary, Instant Recall would pit unsuspecting people in Candid Camera-style hidden camera pranks, culminating with Wink emerging from hiding and grilling the victim with questions about what they had just been subjected to.

Wink had since taken to connecting with fans through social media, with a YouTube channel showcasing games from the past and a Facebook page devoted to discussing them. Periodically, a fan will ask, “When are you going to retire?”

Wink always had the same cheerful answer. “From what?”

On April 15, 2025, Wink Martindale died at age 91…or as we’d prefer to think, he retired. Three years prior to his passing, he reflected on his extraordinary career in an oral history interview for the National Archives of Game Show History, available for viewing on the Strong National Museum of Play website.