With free-agent superstar quarterback Peyton Manning headed to Denver and Tim Tebow to New York, I’m left wondering at the residue that fleeting celebrity leaves behind and how kids at play take in fame and make of it something of their own. And here I turn to my sister-in-law Lynn, who puts the “fanatic” in Broncos fandom. She lives in Boulder and teaches in grade school there, where she’s well-positioned to follow and observe kindergarten kids playing at recess. Last week, during all the trading kerfuffle, Lynn noted boys racing about and then closing in scuffles that ended in a genuflection with a fist grinding into forehead.

Most of the time during recess, Lynn wisely holds back, as like kids everywhere, they need to blow off steam without adults hovering. But this time she wanted to know. “What are you doing?” Lynn asked. “Tebow Tag!” came the response.

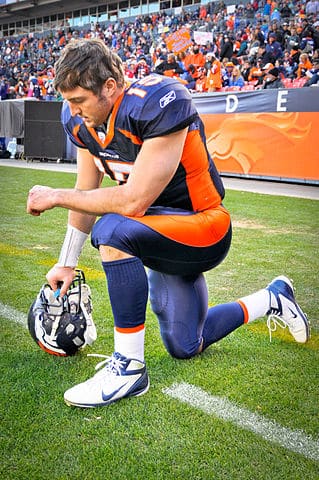

Tim Tebow, a big fellow at 6’4” and 245 pounds, and for Denver a pretty good quarterback who nevertheless had some trouble throwing into coverage, would often genuflect in thanks after a success—a completed long sideline bomb, for example, or a touchdown pass. This prominent devotional act instituted in the late Middle Ages drew the spotlight and earned the quarterback notice in the here and now—sympathy from sports commentators looking for a well-behaved hero, mild disapproval from league officials who regarded even religious displays as personal aggrandizement, and snickers from Saturday Night Live scriptwriters who imagined the deity as a football fan.

Tim Tebow, a big fellow at 6’4” and 245 pounds, and for Denver a pretty good quarterback who nevertheless had some trouble throwing into coverage, would often genuflect in thanks after a success—a completed long sideline bomb, for example, or a touchdown pass. This prominent devotional act instituted in the late Middle Ages drew the spotlight and earned the quarterback notice in the here and now—sympathy from sports commentators looking for a well-behaved hero, mild disapproval from league officials who regarded even religious displays as personal aggrandizement, and snickers from Saturday Night Live scriptwriters who imagined the deity as a football fan.

Now, it’s unlikely that playground lore in Boulder extended to knowledge of the earnest young quarterback’s faith, his mission to preach in the Philippines, or the scrape he got into with the NFL for writing cues to Biblical verses and psalms on the charcoal streaks on his cheekbones. For their part, the kids on the playground misread kneeling, seeing it as a break in the action rather than an act of supplication. And so they went down on one knee in temporary defeat after having been tagged. They imitated the form, and accepted a celebrity endorsement, but their game of tag likely carried along none of the content. “Just like Tebow!” they told my sister-in-law.

Tag is one of those chasing games where much of the fun emerges as roles abruptly reverse, and like most playground games, tag creates rules that kids learn on the fly. Lynn reports: “When they got tagged they had to get down into the “tebow” and stay in the pose until another player who hadn’t yet been caught freed them.” Once tagged, Lynn continues, the emancipator could tag them again saying, “Come on Tebow! It’s game time!” Then they could jump up and get back in the game.” Here it is then, Tebow tag is a variant of Freeze Tag. (Lynn promises to let us know how the kindergarteners will incorporate Peyton Manning into the game.) Once freed from the Tebow posture, the formerly pursued players magically transform into the pursuers, running off at top speed as the rest scatter.

NFL football is quite like a game of tag if you substitute tackling for tagging. But Tebow tag in regard to celebrity is like football in reverse. Celebrity lasts only fleetingly in a game of tag as provisional victors play to give up power rather than attract it.

Tag is reverse football in another important respect; players are not really in it to produce winners and losers. Tag tells a more complicated story about playing. When you’re it—on offense—you struggle mightily to play on defense as quickly as possible. Thus the game provides no easy way to identify winners and losers. Yet skilled tag players still gain in reputation as they demonstrate their speed, their clever elusiveness, their talent for coordinating the game or organizing its rules, or even in gracefully letting the littler kids gain the upper hand. In football, the quarterback measures success in adulation as his troops grind out the yardage; but in tag, athleticism takes second place to socialization. In tag what matters, truly, is how you play the game.