In my first nine months working as the Curatorial Assistant at The Strong, I’ve been immersed in the world of “play” in a way that I haven’t been in a very long time. It’s been refreshing, illuminating, and has caused me to reflect upon my own childhood—how I played as a kid and the ways in which my toys may have shaped my identity as an adult.

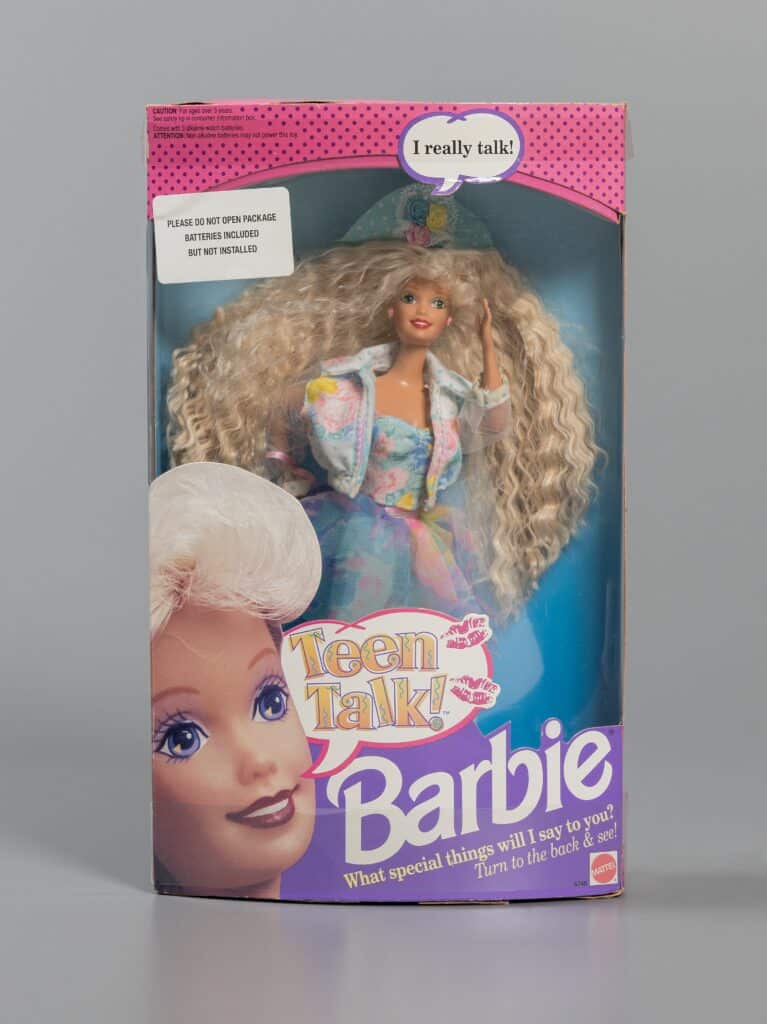

I loved playing with dolls, specifically Barbies, Bratz, and American Girl Dolls. Like many kids, I would create imaginary worlds and interpersonal drama between the dolls. I remember one Barbie in particular that my mom despised. It was the controversial “Teen Talk Barbie,” and I was given it as a gag gift by one of her prank-loving friends. This particular Barbie was unpopular with many feminists of the 1990s (like my mother) because she had a voice box that was programmed with a random assortment of four phrases out of 270 possibilities, including “Let’s plan our dream wedding!,” ”Math class is tough,” “Wouldn’t you love to be a lifeguard?,” and “Want to go shopping?” The math class comment caused the most outrage, with groups like the American Association of University Women and the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics objecting to the phrase, stating that it was detrimental to the efforts to encourage girls to study math and science. It was especially damaging because, in many cases, it was programmed to play right before the phrase about shopping, so Barbie was saying “Math class is hard. Want to go shopping?” Many felt that this perpetuated harmful stereotypes about women being uneducated and only wanting to shop.

The brouhaha revealed that the American public recognized that dolls like Barbie and toys in general can shape a child’s sense of individuality and self-confidence. That’s why Teen Talk Barbie proved so controversial, and why my mom wouldn’t let me play with the one we owned. Dolls like Barbie have a continuous effect on how young girls and women create a sense of identity and are a powerful tool to perpetuate gender norms and stereotypes. As a femme lesbian (a lesbian who exhibits a more feminine gender presentation) who grew up in suburban America, it took me a little longer than many of my queer peers to come to terms with my identity. Everywhere I looked, I saw representations of feminine women as heterosexuals and in heterosexual relationships—including in my toys, and in particular my dolls. These heteronormative representations impacted the way I shaped my own identity at a young age. Reflecting on my childhood, I wish I had had more representation of lesbian and queer dolls, so I could’ve seen my current life as a real possibility at a young age.

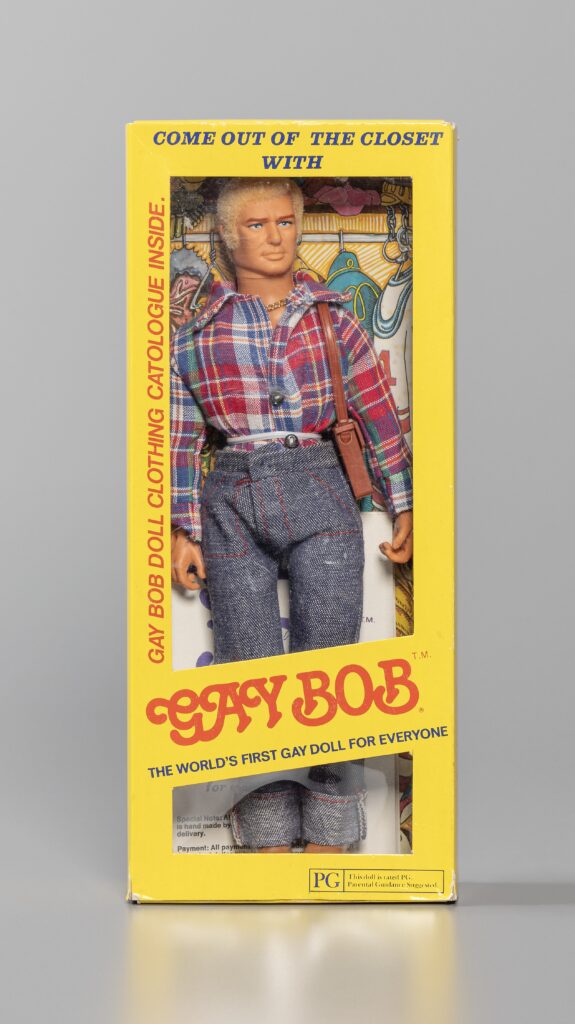

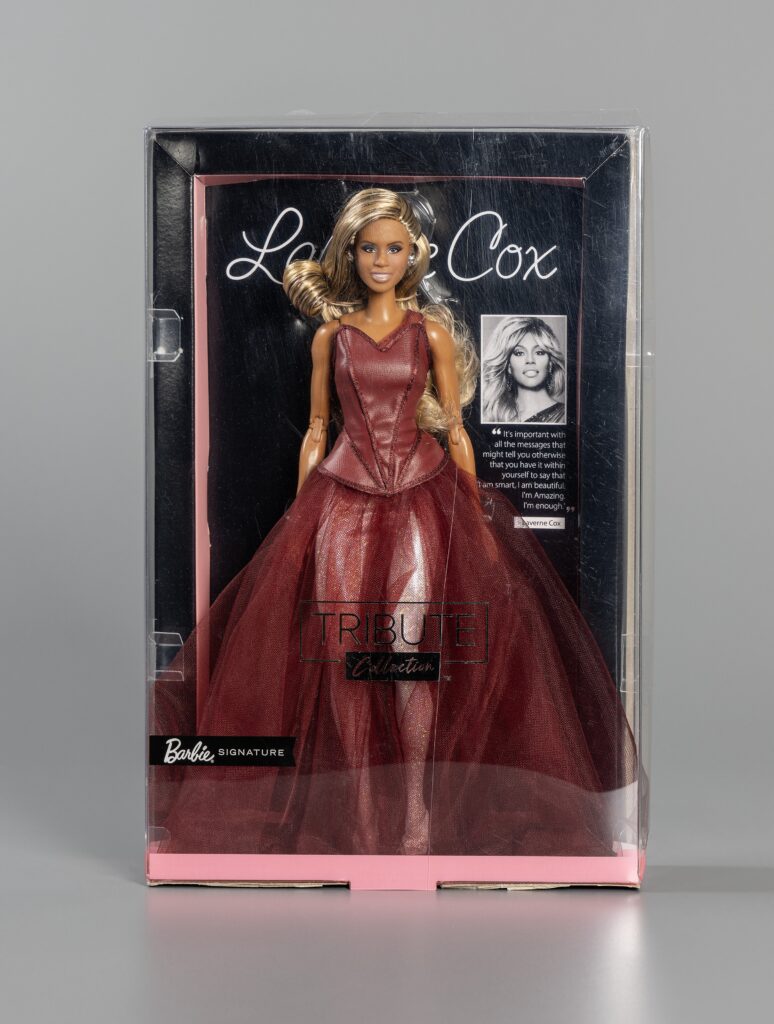

I’m not the first person to realize that there’s a need for queer representation in dolls. A handful of queer dolls had been created since the 1970s to fill this gap: Gay Bob, DykeDolls, and Billy. It’s important to note that these dolls were manufactured for adults, not for children, and all were short-lived products that never reached most mainstream audiences. However, early LGBTQ dolls paved the way for the queer dolls of today. In 2022, the Barbie line added a doll of trans actress and activist, Laverne Cox; Integrity Dolls created a Trixie Mattel doll; and Bratz made history when they released the first-ever set of fashion dolls sold as a same-sex couple. For their 2022 Pride Collection, Bratz partnered with fashion designer Jimmy Paul, who designed bright, playful, rainbow-filled outfits for the couple, Roxxi and Nevra. Nevra and Roxxi had been part of the Bratz Universe since 2003 and 2004, respectively, and they “came out” as a couple via Bratz’s official social media in 2020. Positive representations like Roxxi and Nevra demonstrate to children that lesbian love is a valid part of the world around them.

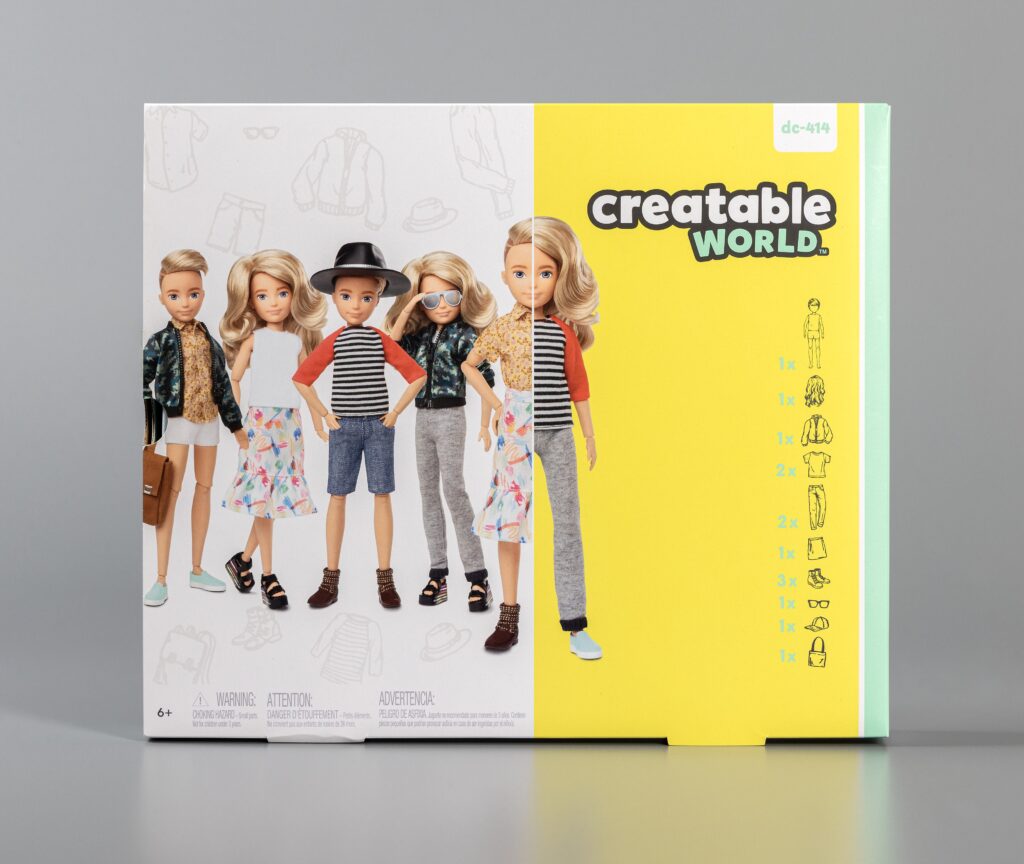

Creating opportunities for children to make their own choices is important to helping them shape their authentic identities. There’s a long history in which children adapt toys—dolls included—to suit their own purposes and play patterns, regardless of what the toymakers may have intended. Mattel recognized that reality and provided children with the opportunity to reimagine dolls for themselves with their gender-inclusive doll line, Creatable Worlds, in 2019. The Creatable World Dolls are designed to be versatile, come in kits with various wigs and clothing, and their bodies do not include features that display an obvious gender. While Creatable World Dolls are not explicitly queer, they allow children the freedom of choice in a way that can reflect who they want to be, who they want to love, and what they want their world to look like.

“It doesn’t take much to chop Barbie’s hair off, switch Barbie’s clothes, pronouns, partners, voice, or story,” says Erica Rand, the author of Barbie’s Queer Accessories and professor of gender and sexuality studies at Bates College. “I think that’s partly why some people fondly remember what they did with Barbie as an early hint of their own queerness, and why adults gravitate to Barbie as a vehicle for play, protest, and parody… However, some people remember being pressured to demonstrate proper gender and sexual tendencies by playing or not playing with her.” Dolls like Bratz and Barbie can have an enormous effect on young people and how we learn to view ourselves within society. I can’t help but think that maybe I would’ve realized my identity earlier in life if I was given a Nevra and Roxxi doll set for my birthday instead of a Barbie that encouraged me to plan my wedding (presumably to Ken). Representation is important and I eagerly await the day when lesbian, gay, and genderfluid dolls are abundant and noncontroversial.