Contemporary travel is a special kind of pandemonium, an admixture of excitement, fear, consumerism, and intense security measures. It can be a rather playful experience too, particularly in the U.S. The stops that took me from Pullman, Washington, where currently I live and work, to The Strong National Museum of Play are a case in point. First it was Pullman to Spokane, then it was Spokane to Las Vegas, where I transferred to a flight to Rochester, New York. To get to the Spokane airport, I hitched a ride north with a Native colleague of mine and his son on their way home to the Confederated Tribes of Colville Reservation to do some hunting. Along the way we had lunch at the Northern Quest Casino & Resort owned and operated by the Kalispell Tribe on a day they happened to be hosting a contest powwow. The wispy jingle of women walking around wearing their jingle-dresses and the din of digital slot machines faded into the background as we joked and told stories over Fat Burgers. The Las Vegas airport was of course filled with similar slot machines, themed just as likely around the majestic buffalo as Netflix’s hit show Squid Game. However upon arrival at the Rochester airport, I couldn’t help but smile when noticing, along with glass display cases celebrating historic play objects, a different kind of playful sound. In this case it was of older arcade cabinets, with their distinctively nostalgic bleeps and bloops, set up by curators from The Strong.

My name is Tony Brave (Lakota and Chippewa-Cree) and I am a scholar of media, play, and games who’s in the throes of writing my dissertation titled United States of Play: A Critical Indigenous History of Play. It spans the late 18th to the 20th centuries, recounting Native/non-Native relations in the U.S. as told through and around historical play objects. With an archive of hundreds of thousands of play objects, what better place to do this research than The Strong? With seasoned advice from my dissertation chair, I applied for and was generously awarded the Valentine-Cosman fellowship through The Strong, which, along with funding from my workplace (Washington State University), afforded what was for me a rather special opportunity to travel from coast to coast and spend two precious weeks digging into archives, engaging with researchers, and playing through The Strong’s numerous exhibitions.

For someone whose life has been deeply touched by play and as a scholar with a keen interest in the subject with normally very little access to such archives, part of me admittedly felt like a Native Charlie Bucket winning the golden ticket to Willy Wonka’s factory. The first day of my visit was on a national holiday and I took the opportunity to experience the museum alongside the hundreds if not thousands of others who made the pilgrimage to the museum on their day off. It was a cacophony of play, as well as labor. Over the course of my stay, I found joy in multiple ways such as sneaking more than a peek into the archives of Atari’s coin-op division, playing Warrior (1979) with the arcade technician (it turns out that buggy vector graphics make for incredible visuals) as well as in somewhat ironically playing as T. Hawk on the Super Street Fighter 2 cabinet. My favorite moment probably had to be hanging out and chatting with the archivist team over chocolate milkshakes. Indeed, play can certainly be joyful but, as scholar Dr. Aaron Trammell persuasively argues in Repairing Play: A Black Phenomenology, experiences of play can and have often been physically or symbolically violent, particularly for BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) folks. That is, throughout U.S. history we have often been either the objects of play or make up the labor and structures undergirding it.

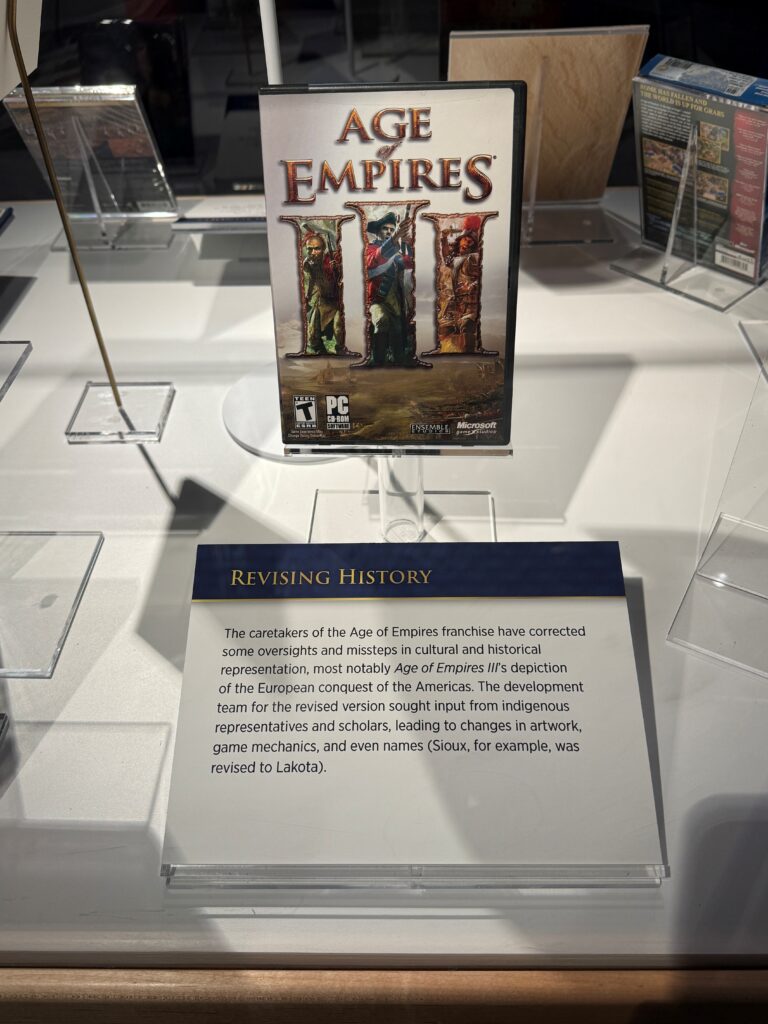

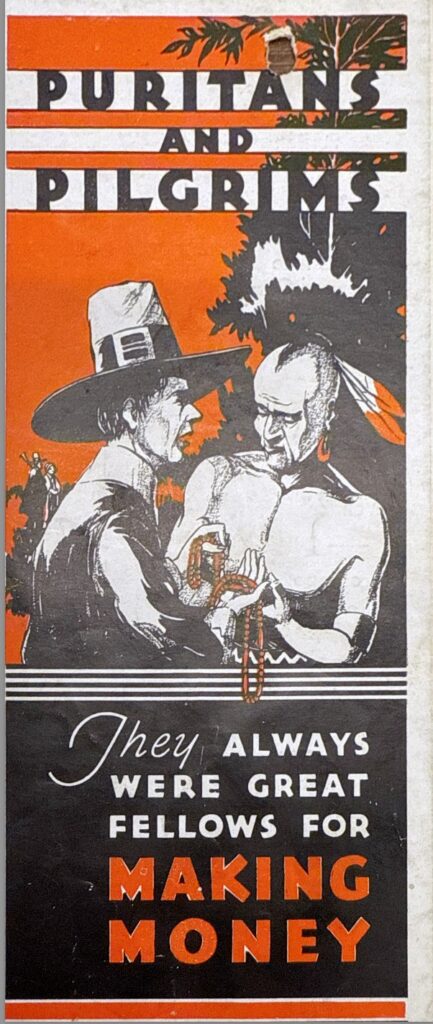

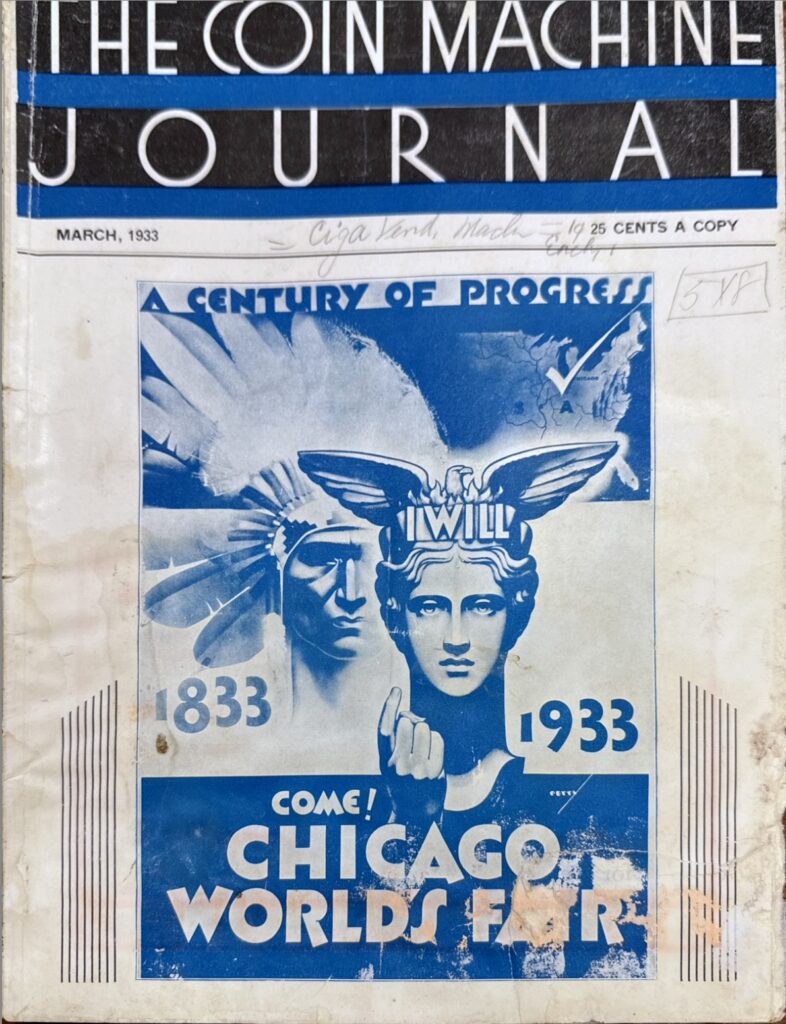

In my research, I try to capture both positive and negative valences of play, highlighting stories of Indigenous joy (i.e. survivance) along with the ways in which play has been used to reproduce settler-colonial ideologies and how these have gotten mixed up over the course of centuries. I was unable to find a great deal of historical evidence of survivance at The Strong. At least not in this visit. When survivance was present, however, it stood out. Being able to, for example, access Anishinaabe artist and game designer Beth LaPensée’s archival collection was a treat along with being able to play in arcade cabinet from another LaPensée creation, my all-time favorite video game When Rivers Were Trails. Standing next to a massive picture of Pascua Yaqui and Cherokee John Romero with the Apple II he used to teach himself how to make games was quite moving. Besides these notable exceptions, the vast majority of materials relating to Native Americans I uncovered at the Strong can be described as, at best, stereotypical, and at worst, well, pretty overtly racist.

This situation, of course, should be understood as more of a reflection of the U.S. than the archive and, despite such blatant racism, I am thankful such materials have been preserved. Still, when I sit down to recall my two-week visit to The Strong, it is not the play objects, trade journals, and the thoughtful exhibitions (rare and inspiring as they are) that first come to mind. It is the people—from the friendly (and surprisingly stylish) security office workers who handed me my visitor badge every morning, the custodial staff who patiently helped me find my way around the Strong’s labyrinth of backrooms when I got lost, the warm hospitality and tireless support of the archivist team (including volunteers and interns), the beautiful auntie at the food court who remembered my favorite order, the research specialists whose expertise and advice on all things play proved indispensable, the research specialist who took the time to walk the museum floor with me, the preservationist who with a wry smile and a few swift clicks of a mouse put in front of me id Software’s infamous Super Mario Bros. 3 clone, upper management staff who were just as eager as I was to put on the gloves and take a look at the objects and to think through settler-Indigenous relations together, to the cascade of excited museum-goers—some of whom felt compelled enough by the experience to randomly strike up conversations with me about their childhood memories of play, or challenge me to a match of Street Fighter 2!

For me, this trip was not just a journey; it was a ceremony. At the risk of essentializing myself, dare I say it was sacred. It was also playful (as if these terms are mutually exclusive). While I deploy classic archival research methods in my research, my approach to research is foremost about building and maintaining equitable, living relationships as best as I can within the scope of my research topic, the limit of my abilities, and my pre-established relations. In my case, in visiting, my goal was not just “intellectual,” but about embodying the ways play has played a role in the longstanding, often inequitable, but nonetheless complex Native/non-Native relations in the U.S. If the opposite of dispossession is connection, then research is much more than simply retrieving, synthesizing, and publishing information. This is because connection requires sustained effort, an acceptance of responsibility, as well as an openness to new experiences. So, when I find out there’s a Women in Games panel happening in the evening that week? Sign me up! Dinner with The Strong’s scholar-in-residence? I’m hungry just thinking about it. A brown bag lunch to chat further with Strong Museum staff? I wouldn’t miss it. An opportunity to give back through a blog post? Well, you’re reading it.

Archived in play spaces, objects, and material relations are histories in need of repair, and such work will not happen until we begin to take collective responsibility for said histories of play. I am happy to report my efforts were returned in kind. I was impressed by the willingness of those whose careers are dedicated to sharing the joy of play to not only confront play’s harsher side alongside me, a relative stranger, but to stand with me, joke with me, challenge me, and to support this research as I trudged through what was for the most part a centuries-long parade of bigotry (with a splash of romanticism) when it comes to Native Americans. Because of this, I can’t wait to make the journey all over again. There’s always more work (and play) to be done.

By: Tony Brave, 2024 Valentine-Cosman Research Fellow