By Adam Nedeff, researcher for the National Archives of Game Show History

A new movie coming out on April 4, The Luckiest Man in America, chronicles one of the most famous (some would say infamous) moments in game show history. Paul Walter Hauser stars as Michael Larson, an ice cream truck driver who made history in the strangest of ways as a contestant on Press Your Luck in 1984. If you want to be surprised by what happened, stop reading now, enjoy the movie, and come back for the full scoop. If you want the details now, though, keep reading this edge-of-your-seat story.

LET’S GO TO THE BOARD

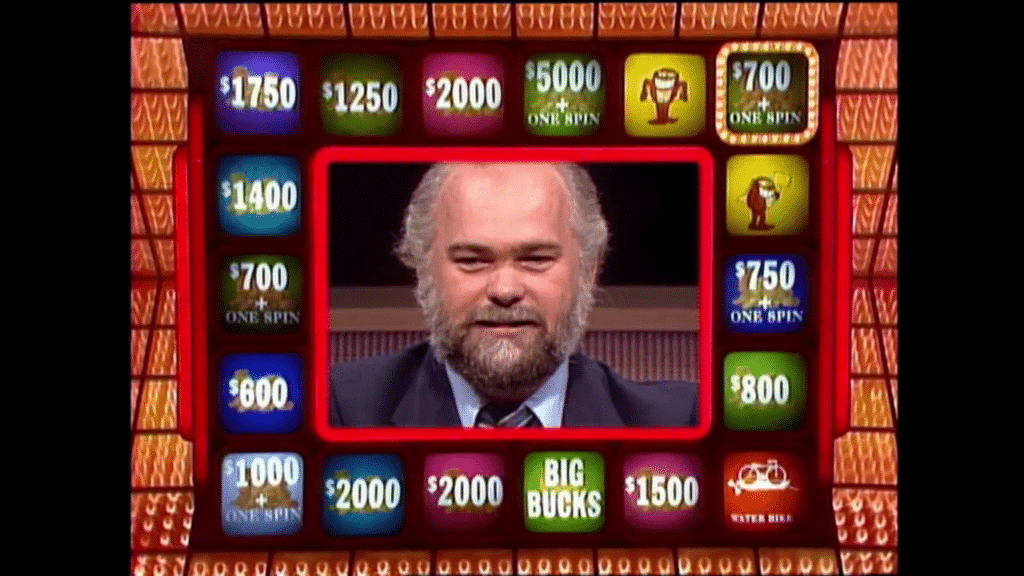

It probably holds the distinction of being the most famous game show of all time, at least that the average TV viewer can’t remember the name of. Mention Press Your Luck and you might get a glimmer of recognition or dazed look. Mention “the game with Big Bucks and Whammies,” though, and faces glow with memories of the larger-than-life game board with every color of the rainbow, surrounded by the frenetic flashing lights, and the whimsical cartoon characters that popped up every now and then to ruin everyone’s fun.

Press Your Luck was a dream combination of “game” and “show.” Sure, there was a flashy set, noisy contestants, blaring electronic music and sound effects, but contained in that eye-popping package was a game perfectly designed to build to a thrilling climax every day, infused with so much fate, so many unpredictable elements, that it seemed there was no such thing as a “runaway game.” Every moment, every turn counted, right down to the very end.

Press Your Luck originally began life as Second Chance, an ABC game show that survived for only 17 weeks. Host Jim Peck welcomed three contestants each day. Peck would read a trivia question and the contestants would write their answers. Peck would then read three possible correct answers and give the players a second chance to write an answer. Writing the correct answer on your second chance earned a “spin.” Sticking with your first answer and being correct earned three spins.

After four questions were played, everybody redeemed their spins on a looming eighteen-square game board. A blinking frame of lights flashed from square to square on the board, almost faster than the eye could see it. Some of the spaces contained cash, some spaces had gift boxes; when landed on, the gift boxes would reveal prizes. The players built up their scores with all those prizes and money. But three of the eighteen spaces were Devils. Landing on a Devil cost the player everything; no matter how far they were into the game, a Devil always cost players their whole haul. A player also had the option of passing spins to the opponent with the highest score. A second round was played, with higher money amounts and more valuable goodies on the board, plus a big money space that could be worth up to $5,000 and an extra spin. No matter how far behind a player was, that available extra spin meant it was always mathematically possible to catch up. Combined with Devils that could wipe out an entire score at any minute, and you had a game that could not possibly decided until the very last spin.

Despite the show coming and going in 95 episodes, creator Bill Carruthers and ABC daytime boss Michael Brockman were confident that he had hit a winning idea. In 1983, Brockman, now at CBS, was looking for a new game and asked Carruthers if he could tinker with Second Chance. The tinkered version was called Press Your Luck. The question round was scaled back considerably to a simple ring-in-to-answer game that sped up proceedings considerably. The spin board was now stuffed with slide projectors that alternated between three options each, for a total of 54 unique possible results on each spin. There were more spaces that offered extra spins, which meant more time spent hitting the button and collecting goodies…or “Whammys,” the funny red blobs that replaced the original Devils. The penalty was punctuated nicely in Press Your Luck. When a contestant landed on a Whammy, there was a brief time-out for an animated Whammy cartoon, with the Whammy mocking the contestant, activating weapons (which usually backfired), or referencing trendy songs and TV commercials.

Carruthers also made a slight aesthetic change to the board; the flashing light now blinked from square to square a bit slower. It still moved fast enough that contestants couldn’t really make sense of where the light was until they hit their button to stop it; it just wasn’t moving with the strobe-like speed of Second Chance’s light.

Early in the developmental stages of Press Your Luck, Bill Carruthers made it known to CBS that he wanted the lights to be controlled by a computer system that could handle 12 patterns in which the light could flash. With the technology available at the time, a computer system that could truly randomize the light would have been prohibitively expensive, but Carruthers thought that a computer alternating between a dozen patterns could create the illusion of randomness convincingly. CBS agreed to the suggestion initially.

When the Press Your Luck pilot was shot, Carruthers was given a system that had five patterns. Carruthers said that would do for the pilot, but if CBS picked up the series, he needed a dozen of them. But when CBS put Press Your Luck on the schedule, Carruthers went to his new network bosses and reminded them of his request.

“We just don’t have the money for it,” he was told. “We can only give you five patterns.”

Carruthers, in a prescient moment, warned the network, “I want to go on the record right now, I believe if we only have five patterns, we’re going to have a situation where a contestant memorizes the board.”

The retort came from another staffer in the room: “We should be so lucky if we get viewers who care about this show enough to watch it every day and memorize the way the lights flash.” Carruthers’ warning, was forgotten about until May 19, 1984, a day when Carruthers, who served as his own director, watched the game in the control room, saw what one contestant was doing, and pulled off his headset in exasperation.

“He’s done it,” Carruthers announced.

HERE COMES THE ICE CREAM MAN

Michael Larson was an eccentric Lebanon, Ohio, native whose mother optimistically described him to the Cincinnati Enquirer as “…[E]xtremely smart and very intense. Once he gets his mind set on something, nothing deters him. He follows through on anything he sets out to do.”

His brother, James, had a grimmer assessment, later telling Game Show Network, “He was doomed to self-destruction.”

In his younger years, he seemed musically inclined, playing the organ and singing with a jazz band. But by day, Michael Larson worked various odd jobs during his adult life, never concerned with finding a career and far more interested in finding a get-rich-quick-scheme that would set him up for life. He spent the better part of ten years driving an ice cream truck, which meant that he was rendered unemployed every year when autumn and winter struck Ohio. Larson spent his days watching a bizarre arrangement of multiple televisions and VCRs in his living room. It wasn’t a matter of vegging out, his common-law wife later remembered; he seemed to be watching all of the sets as if he was searching for something; he just didn’t know what it was.

Larson found Press Your Luck shortly after it bowed on CBS in September 1983. He became fascinated with it, to the point of watching it and recording it daily to re-watch the games later, and after a few months, Larson figured out Bill Carruthers’ big secret. Larson spotted the patterns.

Larson bought a plane ticket and took a journey to Los Angeles to visit the Press Your Luck production office. There, he met contestant coordinator Bob Edwards and show creator Bill Carruthers. Larson, a natural born salesman, won over Carruthers quickly with his tale of flying out to Los Angeles just to be a contestant on his creation.

Edwards was wary. After Larson left, he voiced his concerns. “There’s something about this guy that worries me.”

Carruthers liked Larson, and admitted later that he should have trusted his contestant coordinator’s gut.

ATTACK ON THE SHOW

Larson’s memorization efforts were focused mainly on two of the eighteen spaces of the board. One square would cycle between $1,000, or $1,250, or $1,500 in round one, and then $3,000, $4,000, and $5,000 in round two. The other square cycled between $500, $750, and $1,000 in round two. And in round two, all of those cash values had extra spins attached to them. Larson didn’t necessarily know WHAT he’d land on when he pressed his button, but as long as he landed on those two spaces, he knew that, #1, he would never hit a Whammy, and #2, his turn would never end because he’d keep piling up those extra spins.

Behind the scenes, chaos erupted. The control room was packed with staffers and CBS executives who had all figured out exactly what they were watching, but nobody could grasp for a reason to stop it from happening. So even after Carruthers declared that Larson had gamed the system, everyone recognized that the only thing they could do was keep tape rolling, even though Larson was about to take his 30th spin and that the taping for this 30-minute game show was approaching the 45-minute mark.

Larson had already set a CBS daytime game show record when his score reached the $80,000 mark, but he kept going until he crossed the $100,000 mark. Larson would later admit that he suddenly went blank when he hit six figures and couldn’t remember the patterns anymore; the past hour left him mentally spent. He passed the spins to his opponents. Disaster almost struck when they passed spins back to him, but Larson survived on pure luck and finished the game with $110,237, almost entirely cash. (He also got a sailboat and a vacation in his till.) CBS executives and lawyers desperately searched for something or evidence that Larson had cheated. They wanted to find a rule to say that he wasn’t entitled to the winnings, but the efforts were in vain. Larson had played the game perfectly ethically and just beaten the system.

Robert Noah, another venerable game show producer, told TV Guide, “What everyone was finally forced to acknowledge was that what he did was legitimate. It was like being a card counter at blackjack. After all, nowhere in the rules did it say that you couldn’t pay attention.”

CBS edited the game and spread it out over two days, but the network was so embarrassed that a contestant had beaten their system that they aired it with no fanfare. In the coming years, reruns of Press Your Luck would go into syndication and on USA Network, but Larson’s games were never included in the rerun packages. His amazing performance evolved into something of an urban legend; he was errantly blamed for the show’s cancellation. In some circles, the story went that CBS cancelled the show because Larson drained the network of so much money. It was actually just the opposite; word of mouth triggered a ratings spike for Press Your Luck in the months following Larson’s performance, and the show stayed on the air for two more years.

AFTERMATH

For obvious reasons, Bill Carruthers finally got his wish, and then some. CBS enhanced the computer system and added 20 more patterns to the game board. A short time later, Larson curiously called Bob Edwards’ office and asked if the show was planning on having a tournament of champions any time soon. Larson’s inquiry was politely ignored.

But amazingly, tragically, the reason Larson wanted to come back was because his money was already gone. After paying income taxes, he still had a pretty good chunk of money left, about $70,000. As Larson’s common-law wife later recalled, things went seriously wrong because of a “radio contest,” although the contest she described sounds suspiciously like something another game show, Sale of the Century, did later in 1984. The show offered a $40,000 cash jackpot to contestants who mailed in $1 bills with serial numbers that matched a pre-determined series of digits. Larson went to the bank, withdrew a significant amount of money in $1 bills and brought it home in grocery bags, so he could go through the whole pile every day. One night, he and his wife left the house. When they came back, the grocery bags were gone. Whatever was left after the burglary, Larson lost in a failed real estate investment.

Larson’s life would take some mysterious and bizarre twists in the coming years. Larson, who admitted to Peter Tomarken after the game that he couldn’t afford to buy his daughter a present a few days earlier, promptly bought some toys and sent them off to her. And then he vanished for a while. When the area newspaper tried to write a story about the local boy who made good, they couldn’t reach him.

His mother told the paper, “He just took off Sunday night by plane on a vacation. I have no idea where he went but I’m sure it’s towards the west coast.”

Over the next decade, most of his family had no idea where he was even living. FBI agents contacted his brother one day asking if he knew Larson’s whereabouts. Larson resurfaced briefly in 1994 after the release of the film Quiz Show. The film’s focus on the quiz show scandals of the 1950s reignited interest about the noteworthy contestant of 1984 who had swindled a game show. Larson appeared on a few news and talk shows and granted an interview to TV Guide, enjoying the 15 extra minutes of fame that the movie afforded him. But the movie left theaters, the interest faded away, and so too did Michael Larson. On February 16, 1999, Larson died at age 49 from throat cancer. When his family was notified, it was the first time any of them learned that he had been living in Florida, more or less hiding from the FBI and the SEC, due to his possible involvement in a telephone-related con game.

Larson’s triumph and tragedy were chronicled in a 2003 Game Show Network documentary, titled Big Bucks: The Press Your Luck Scandal, a project overseen by NAGSH co-founder Bob Boden.

In April 2025, the wide release of the film The Luckiest Man in America, starring Paul Walter Hauser as Michael Larson, will immortalize the story on the big screen.

DO YOU REMEMBER…THESE OTHER MOVIES INSPIRED BY GAME SHOWS?

Confessions of a Dangerous Mind (2002): Based on Chuck Barris’ “unauthorized biography” about his claims that he was a CIA assassin during his years of producing and hosting shows.

Legends of the Hidden Temple (2016): More than 20 years after the original series ended, Nickelodeon unleashed a delightful made-for-TV movie about a group of kids who wander into an abandoned amusement park attraction and discover it’s Olmec’s temple.

Quiz Show (1994): A dramatization of the turmoil at Twenty One during the quiz show scandals, and how contestants Herb Stempel and Charles Van Doren were affected.